Media Forum Closing. Lecture by Peter Greenaway

About Media Forum

Schedule

Exhibition "The Immersion: Towards the Tactile Cinema"

Educational programmes

Media Festivals: Let’s Rock! Programme

For Press

Partners

Contacts

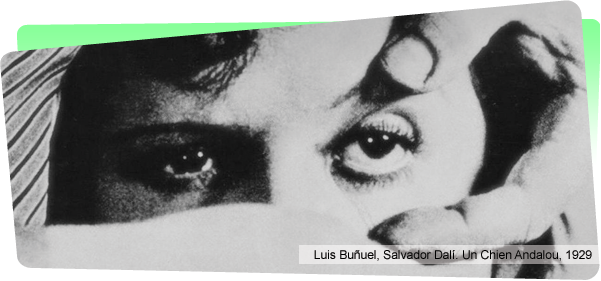

I. Pure Cinema

Pure Cinema, the first section of the exhibition, is a responce to the “art for art’ sake” concept. Here screen is used as a canvas, actually presenting cinema as an apotheosis of painting. Works by Kazimir Malevich, Mikhail Matyushin, Nam June Paik, Ken Jacobs, Paul Clipson, Hans Richter, Konstantin Adzher, Oleg and Olga Ponomarev are presented.

Mikhail Matyushin

Mikhail Matyushin

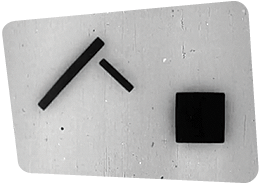

Colour tables

Russia/USSR, 1914—1929 Color print, 10 prints, 600x600 mm each

Picture © Государственный музей истории Санкт-Петербурга, Санкт-Петербург, 2012 г.

“The defining formula for artistic and scientific work of Matyushin (1914—29) was “spatial realism”, i.e. understanding of the visual art as a spatial culture. <...> When cubists and suprematists made their non-figurative compositions according to the laws established on the ground of the modern french painting’s formal analysis, Matyushin with his working group rather continued the traditions of french cubism and impressionism (exaggeration of the eye role — “expanded looking”, immediate sensation, intuition etc.). <...> Matyushin began the research of colour in different conditions of spatial environment on the models of different forms and colours. Thus the following questions were raised: colour and form deformations depending on the model’s situation in the space and physiological conditions of looking, the role of movement in colour perception, the interaction between colour and form etc.”

M.Ender. “M.V.Matyushin. The regularity of colour relations’ alterability. // Colour reference book. Moscow-Leningrad, 1932, p.7

“A few more words on the study of the colour in motion. It happened that the bright moving spot, being included in general examination, becomes brighter itself and raises the chromacity of the environment. And vice versa, if we change the way of examination in the same conditions of the movement, i.e. will watch narrowly with the yellow spot, throwing together all the attention into the central point of the moving spot; if we wouldn’t pay any attention to the environment, when the spot itself and the medium in which it moves, begin to die out in the same intentive way. The conclusions made out of this experience give us the following statements: 1) While watching the colour in motion by the method of expanded looking, the general chromacity becomes brighter. 2) While watching the colour in motion by the method of central sight, isolated from the colour medium, chromacity becomes more dull.

M.V. Matyushin. The regularity of colour relations’ alterability. // Colour reference book. Moscow-Leningrad, 1932, p.23

Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp

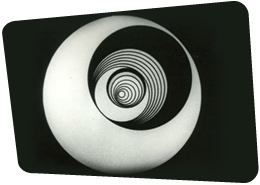

Anemiс Cinema

France, 2012 7', movie, b/w, silent

© succession Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris 2012

"Duchamp could not avoid using the incipient art of cinema as an instrument for continuation of his global experiment of breaking the human perception. In this respect Duchamp's cinematographic project, which consists of relief notes alternating with images on rotating disks, is a multi-level play with space and awareness. The title of the movie itself implies the possibility of the polisemantic reading. The word combination "anemic cinema" may be read as a tautology. At the same time the word "anemic" may denote a quality of the viewer's reaction. On the one hand it describes a hypnotic state, a dissotiation of mind induced by the contemplation of this piece. On the other hand it is about lack of the conscious, when the mind switches from one layer of meaning to another, some kind of automatism caused by the viewer's life in the alphabet society. The first and the most evident layer of the play is when a spiral acquires the features of the three-dimentional space while rotating. The middle of the spiral in the movement creates an illusion of the linear perspective, touching the perception of the viewer and pulling it inside, thus creating virtuality around the observer. The second layer embraces linguistic games with written words based on alliteration. The spiral movement of close to omonimity words creates an illusion of overflowing of one word into another. At the same time morpheming of the meaning of the words takes place. The viewer's perception starts to translate the meaning of the written words, building a certain reality in the mind, different from the shown object. The changing of the meaning at every moment places reality into a new context thus creating the effect of dissotiation, illustrating Duchamp's wish to show the limitedness of human consciousness. He also uses mirroring word combinations, the direction of reading of which is defined by the direction of the movement of the rotating surface, which also shows that perception may be governed. The viewer becomes able to become aware of being governed by outer events, thus putting into question the modernist assertion of the omnipotence of the human mind. And finally, on a deeper level, the collation of the two assembled sections with words and the spiral introduces the play based on the difference of the human perception of an object and a linguistic sign, although similar to it in its form. Visual similarity between the drawing of the spiral and the spiral writing of the words as images leads a person to use different means for decoding information: she alternates reading and contemplating while the percepted image remains relatively monotonous. Also if we take into account the specificity of the silent movie of that period, the viewer perceived the subtitles as the commentaries to the previous episode, therefore the successive show of such sections leads to the cinematographic Kuleshov's effect and the birth of the third meaning from the two shown images."

Roman Putyatin

Oleg Ponomarev (upon the script by Kazimir Malevich)

Oleg Ponomarev (upon the script by Kazimir Malevich)

Painting and the Problem of the Architectural Approximation of a New Classical Architectural System

Russia, 2012

4'18'', video installation

Courtesy of the artist

The script was presumably written by Kazimir Malevich in the USSR for a popular-science film. It embodies Malevich's understanding of the essence of cinema. also formulated in his articles "Faces rejoice on the screen", "Artist and Cinema", published in the Cinema Magazine ARK which was printed in 1925—26. in 1927 Malevich brought the project together with his archive in 1927. After meeting one of the founders of the "abstract cinema" Hans Richter (1888—1976) in Berlin and seeing his films Malevich became more confident in his ability to realize his script. However Malevich did not manage to discuss it with Richter because he did not know German and stayed in Berlin only for a short time. He received an order to return to the USSR and added a note to the script saying "For Hans Richter" (on a separate sheet). The script was discovered in the late 50-ies by Werner Haftmann who was sorting Malevich's archive, which was left in Berlin in 1927 with von Risens. Hans Richter was informed of the discovery of this script but could not remember the episode of cooperation with Malevich which he admitted in his memoires. In the end of his life, in 1970, Richter bagen to make an animation film based on Malevich's script, but the project was not finished. The script on three sheets with schematical coloured drawings, is preserved in the collection of Chviklitser, Baden-Baden, Germany. The text of the script was first published as a facsimile with a French translation in the edition: Czwiklitzer С. Lettres autographes des peintures et sculptures. Basle, 1976. R 487-488. Russian text is printed in Малевич К. Художественно-научный фильм "Живопись и проблемы архитектурного приближения новой классической архитектурной системы" / Публ., подгот. текста и коммент. А..С.Шатских // Малевич. Классический авангард 3. Витебск: Сб. / Сост. Т.В.Котович. Витебск: Областной краеведческий музей, 1999. С. 33-40.

Hans Richter

Hans Richter

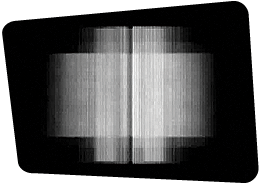

Rhythmus 21

Germany, 1921

3', film, b/w, silent

Film in the permanent collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2012 Hans Richter

Richter and Eggeling were among the first creators of abstract film. Although the films themselves were produced in Berlin, the works were grounded in Zurich Dada’s experiments with abstraction. The artists originally experimented with painting on scrolls before turning to animated film. Eggeling directly transposed his scroll drawings to film to create "cinematic drawings"; Richter more fully exploited the new medium, abandoning his drawings altogether and filming paper rectangles, squares, and lines of various sizes and shades suggestive of movement and depth. "Rhythmus 21 is Hans Richter's first film... Richter went on to make Rhythmus 23 (1923)... and Rhythmus 25 (1925). In this first of the series, originally known as Film ist Rhythmus, he experiments with square forms. These forms appear in very simple to very complex compositions — from the beginning shots where the squares occupy the entire screen, to compositions with squares with the frame. The effect is a subversion of the cinematic illusion of depth. Richter creates a precise rhythm with the movement of these shapes. "The simple square of the movie screen could easily be divided and 'orchestrated,'" wrote Richter in 1952. "These divisions or parts could then be orchestrated in time by accepting the rectangle of the 'movie canvas' as the form element. In other words, I did again with the screen what I had done years before with the canvas. In doing so I found a new sensation: rhythm — which is, I still think, the chief sensation of any expression of movement."

Circulating Film Library Catalog, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1984, p. 166

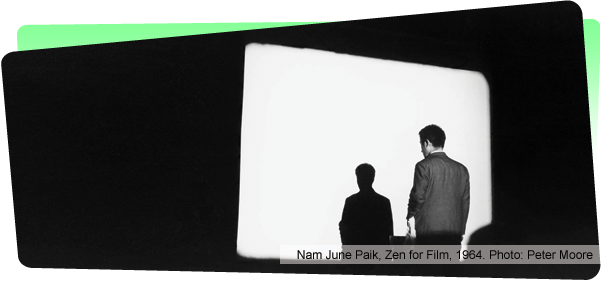

Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik

Zen for Film (Fluxfilm n°1)

USA, 1964

Video, loop

Nam June Paik, Zen for Film (Fluxfilm n°1), 1964, Film, Collection Centre Pompidou, Dist. RMN / Image Centre Pompidou, Photo by Peter Moore © Estate of Peter Moore/VAGA, NYC and Nam June Paik Estate

“In an endless loop, unexposed film runs through the projector. The resulting projected image shows a surface illuminated by a bright light, occasionally altered by the appearance of scratches and dust particles in the surface of the damaged film material. As an analogy to John Cage, who included silence as a non-sound in his music, Paik uses the emptiness of the image for his art. This a film which depicts only itself and its own material qualities, and which, as an «anti-film,» is meant to encourage viewers to oppose the flood of images from outside with one’s own interior images." Heike Helfert

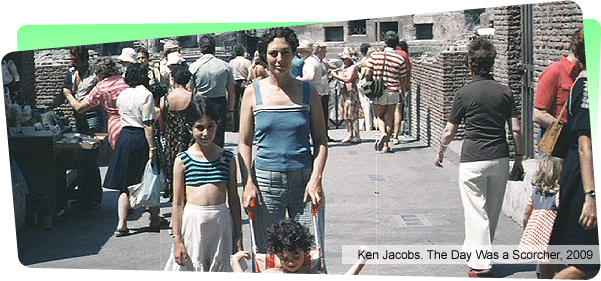

Ken Jacobs

Ken Jacobs

Disorient Express

USA, 1995 30', b/w, silent

Courtesy of the artist. Original 1906, U.S. Library Of Congress; 1995, Ken Jacobs, assisted by Florence Jacobs. (35mm. optical-rephotography by Sam Bush, Western Cine, Denver).

"I've been raiding the Paper Print Collection of The Library Of Congress in Washington, D.C., since the late '60's with TOM, THE PIPER'S SON. It's a preserve of early cinema. Until 1912, in order to copyright a film, one deposited with the Library a positive from the negative printed on paper, unprojectable, but -unlike nitrate printscapable of weathering the years without crumbling into chemical volatility. And there the stacks rested, safely out of mind, hundreds and hundreds of silent rolls most less than 30 meters, many Edisons, American Mutoscope and Biograph, Gaumont, Lubin, Vitagraph...; cinesnatches of life as it was lived, vaudevillians, protodramas, and too many state parades. Until they were ripe for rediscovery and reevaluation, and rephotography back onto film. Kaleidoscopic symmetry in DISORIENT EXPRESS is not an end in itself. The radiant patterning that affirms the screen-plane serves also to provide visual events of an entirely other magnitude. Flat transmutes repeatedly to massive depth illusion; yet that which appears so forcefully, convincingly in depth is patently unreal -an irrational space. The obvious filmic flips and turns (method is always evident) of the scenic trip provide perceptual challenges to our understanding of reality, and we are often unable to see things as we know they are."

Ken Jacobs

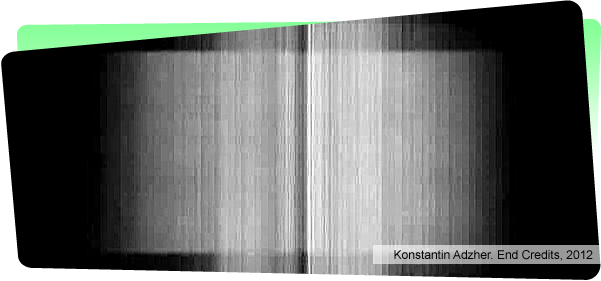

Konstantin Adzher

Konstantin Adzher

End Credits

Russia, 2012

2'45'', video, sound

Courtesy of the artist

End credits are added at the end of a motion picture, television program, or video game to list the cast and crew involved in the production. Wikipedia "At the first sight end credits of motion pictures are somehow imposed on a viewer as a formal technical addition to the movie. While they are being screened, the light in the cinema is switched on, and in illegal copies they are often omitted. The substantial amount of text is screened at a high speed, which naturally makes reading difficult and demonstrates the purely formal character of the end credits. They acquire autonomy, merging into abstract graphical structures. But the end credits also have another function. The serve as a passage, an edge between the movie and the reality. The viewer can experience the after-taste of the film, see it and feel again at the high speed inside her own memory. Video work "End Credits" is such traces of the trajectories of the end credits of motion pictures. They merge and mingle with each other, creating new independent forms of concentrated cinema".

Konstantin Adzher

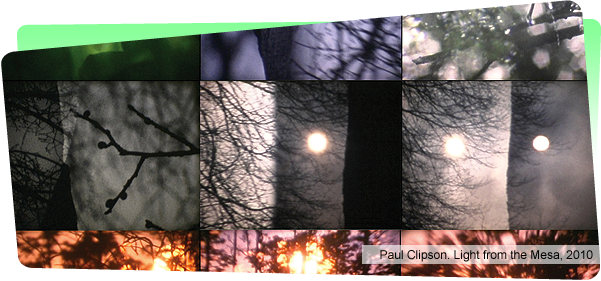

Paul Clipson

Paul Clipson

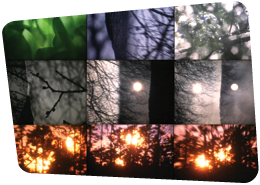

Light from the Mesa

USA, 2010

6', super 8mm film (screened on DVD), color/b/w, with stereo sound

Music by Barn Owl

Courtesy of the artist

"Darkness envelops. A click, followed by the steady rhythm of the projector performing its incessant task of advance-pause-advance. Text: Light from the Mesa the only linguistic sign we will be given. Then, the screen explodes green, and the air becomes instantly pressurized with the force of the musicians’ opening sonic swell. In an instant we have moved from darkness and silence into a swirling mass of spectral luminance and moving air. I am hyperaware of my body, my senses, my surroundings. Yet I am slowly drawn into the experience, towards the light and into the sound. <...> Paul Clipson works primarily in Super-8 film, and generally exhibits his films as a live collaboration with musicians or sound artists. The projector is rarely, if ever, isolated in a projection booth; it is as much of the performance as the musicians and the filmmaker. Richly textured and formally dense, all of the super-impositions and editing takes place within the camera while he is shooting. Oftentimes he does not know the piece the musicians will be performing, as the musicians also rarely know what piece he will be showing. Part of his practice is then the blind symbiosis of sound and image, a union performed with the congregation of the audience as witness."

Kent Long